My Name (Is My Daknam) Is My Name

"Why do you go by 'Preet' now?"

Sometimes chosen, sometimes given, our names are an important first impression into who we are. Brown kids from our generation often modify their social media handles with food puns or repeated letters to make themselves more palatable. We go by different names to be seen at work, at school, on resumés and job applications, dating app profiles, at coffee shops, on calls with customer service representatives, and more. Some see this practice as a concession to an anglicized world that wouldn’t care to learn the right pronunciations, though I think there’s more to it.

But in reality, of course we do that! Our names provide others with context and associations with who we are, and if it’s hard to say or remember our names, it’s harder to remember us in the English-speaking world.

It makes sense why and how we do it, and to a lesser extent, where we have to do it and where we don’t. But who are we, and are we losing ourselves in the process? Or are we just inventing new versions of ourselves that garner more attention than do these foreign, multisyllabic hard-to-pronounce cultural paperweights?

I owe much of my personal development to Jhumpa Lahiri. Throughout her expansive short stories, compelling historical fiction and biting contemporary Italian litfic alike, she provided me with lenses to process various aspects of my being. My favorite book of hers, The Namesake (+Mira Nair’s film adaptation), captures the oft-hidden beauty of our names as well as how we use them in the Western spaces we inhabit.

The Namesake’s story is framed around a Bengali cultural practice wherein one is given a “good name” at birth, to be used professionally and externally, and a “daknam” (nickname) used by friends and family. “Good names” and “daknams” remain fixtures of Indian culture, reflecting an important distinction between how one is to be perceived by society-at-large versus by one’s family at home.

In our culture, to the outside world, you’re this auspiciously, often astrologically named person who intrepidly carries the family surname with your venerable given name. But to your loved ones, and especially to your elders, you’re a “little one” in the same way your dog or cat might be – hence the term “pet name.”

Just about every brown person I know, Bengali or not, has a pet name used endearingly by family and close friends. My dad’s pet name is Bobby. My mom’s is “Sonu,” which means “beautiful.” From “Samu” to “Nonu” to “Mimo” to “Paro” to “Rayee,” these cutesy one-to-two-syllable attributions reflect familial affection and close ties. They can also be quicker to say for those of us blessed with names triple or quintuple the length of your typical “Alex” or “Sally” or “Jack.”

Daknams are a minor aspect of our culture, but nonetheless an important one. Your elders calling you by a term of endearment is the other side of this ubiquitous bidirectional familial piety that also manifests in you touching their feet to greet them. Pet names reinforce bonds and frame each family member as part of a collective unit, where each family speaks its unique vernacular to underscore closeness. I still call my oldest cousin in India “Gonu,” as does the whole family. It doesn’t matter that he’s married or over 30. He is inextricably tied to the name in the same way our minds are tied to our bodies. The name will never leave him, and he will never leave it.

Both adaptations of The Namesake especially spoke to me as I’ve been using nicknames throughout my life. My birth name “Jaspreet” means “one who sings praises of God.” I take that as me being named after the musical masters at every Gurdwara belting their hearts out at kirtan while they wail on their rustic harmoniums. My dadi is a Simran fanatic, after all.

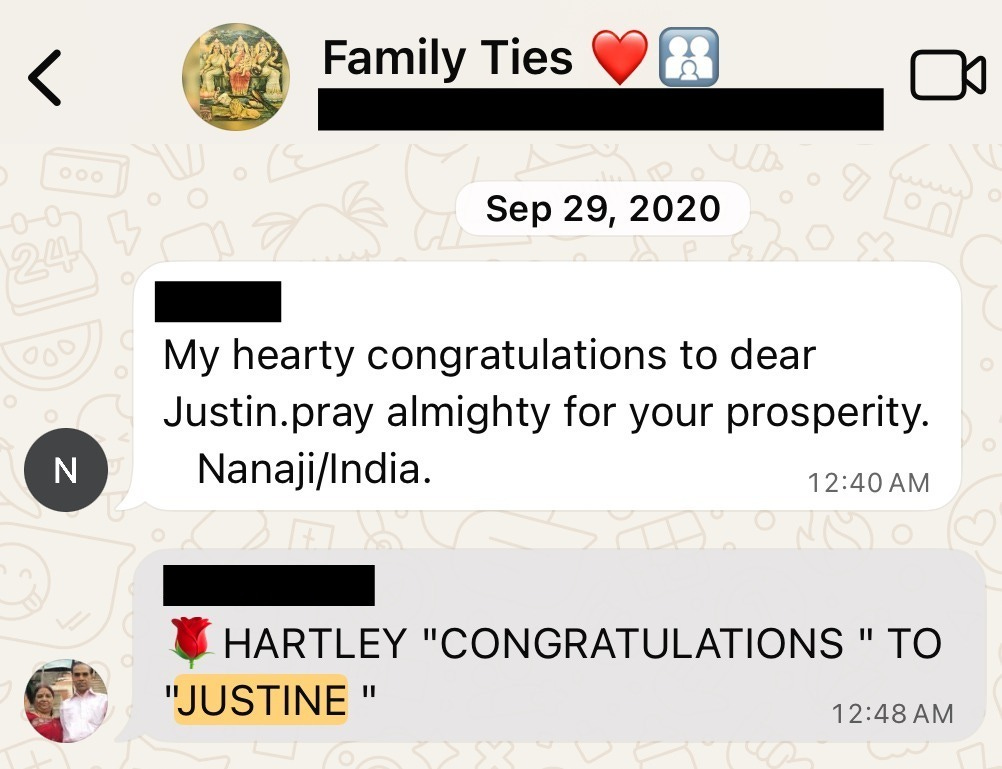

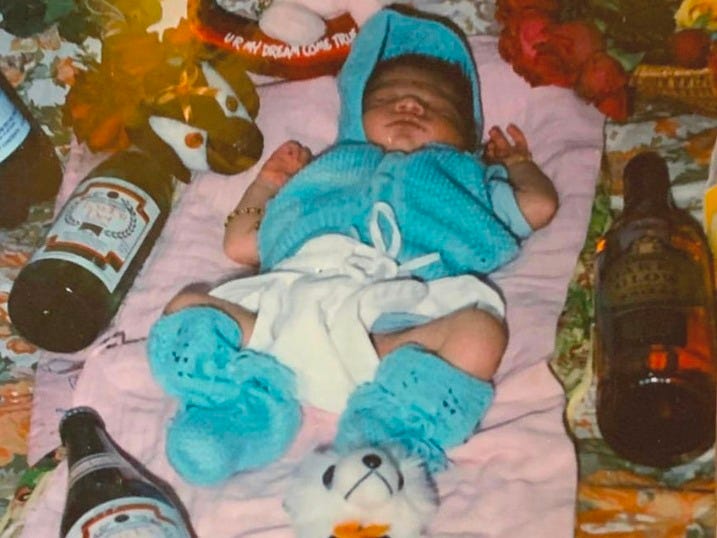

My pet name since birth has been “Justin.” I’ve gone by this name for the vast majority of my life, since before I could remember. Even my extended family back in India still calls me “Justin” on WhatsApp messages, often pronouncing and even spelling it as “JUSTINE.” Growing up, I only really heard “Jaspreet” when new or substitute teachers would call roll. I swiftly corrected them every time – “I go by Justin.” “You can call me Justin.” “Just ‘Justin’ is fine.” And so on.

Having been raised in America, it was only natural that my pet name came to be the easiest way to refer to me. It’s a lot easier for the average American to say than “Jaspreet” is. Plus, it would irk me when people would mispronounced it. I liked “Justin” way more than poorly anglicized attempts like “Jazz-preet” when it’s actually more like “jus-preeth.” To avoid frustration, I gave up and stuck with “Justin” throughout school, college and at work. It had come to embody me.

I never understood why fellow brown kids weren’t as quick to accept me, or why their demeanor towards me would change when I gave my name as “Justin.” Over time, I came to realize it was an instant filter-out for them – because I went by a “white name,” I instantly couldn’t be “brown enough” or “Indian enough.” To their knowledge and quick judgment, I wouldn’t be as “cultured” or “true to myself” because I probably “chose the name myself.” They would see me as whitewashed based off of nothing but a nomenclature I never consented to in the first place. I was so used to being called “Justin” that I internalized it and never looked back through most of my life.

The first time someone insisted on calling me “Jaspreet” was in college when I met my friend Krunal for the first time after a South Asian Studies class. He had followed me after class and asked me for my name. I reflexively said “Justin,” which he reflexively rejected out of pride for our shared culture. He, like many others, had instantly made a judgment based on my name. But when I told him that it was a pet name, like how his parents call him “Kunu,” he understood, but stayed firm on using my given name.

This inspired me to go by “Jaspreet” in that class because it felt right given the subject matter. Krunal’s unwavering respect for our shared culture pushed me out of my comfort zone — though it meant little to me at the time, it sowed the seeds for a transformation. Throughout the rest of college, he and everyone he introduced me to called me “Jaspreet.” He still uses “Jaspreet” to this day, almost a decade later. It makes me smile every time.

I’ve been living in Washington, DC for almost five years now, and have used “Justin” virtually the entire time. It was only amid a particularly traumatic 2024 that I decided I needed a reset. Simultaneous struggles with interpersonal and professional relationships, my mother’s declining health and my uncle’s passing forced me to undergo a personal transformation in order to recuperate. Last summer, I broke down the barriers of my capacity, dedication and diligence to pull myself out of several holes at once. It ended up bearing fruit for me as I was able to bounce back and reclaim agency of my life — my mom is also doing much better now!

The associated emotional and mental stress of this time caused me to re-evaluate how I see and portray myself as well how I want others to parse my existence. I thought hard about how I want to develop my identity leading into my late twenties and onward. My mind immediately went to the hit show Severance, wherein employees at a shady conglomerate separate their professional and personal consciousnesses when stepping in and out of the office.

I felt the need to do something similar, keeping “Justin” as my work/coffee shop name and using a different name for everything else. “Jaspreet” felt too obvious/“hard to pronounce,” and I wanted to be able to go by what felt comfortable for me. I landed on “Preet” — another name that a few friends and loved ones had offhandedly referred to me as in the past. “Preet,” meaning love, cuts across all aspects of my life.

I strive to imbue my friendships, relationships, family, and community with genuine love, care and support. I stand as a rock for people I cherish when they are in need. I feel like I embody “Preet” on multiple levels. It felt right to create this Desi “outie” on my own terms, scoffing at those who judged me for “choosing” the name Justin by creating something new entirely out of my daknam.

It’s the same kind of thing that grounds me when I make Indian food or watch Bollywood. Third-culture kids like myself are known to stand out instead of just assimilating as our parents did. Yet, our parents and grandparents remain so proud of our culture contexts, which manifests in them invariably passing down our shared languages, foods, arts, religions and more. And unsurprisingly, first-gen kids and children of immigrants often return to these touch points that we previously shunned.

In that measured return to our heritage, we harken back to growing up in Gurdwaras, temples, mosques, Sunday language classes, eating food at home, going to family friend parties and more. They shaped us and formed many of our early associations, and they ground us as we navigate the countries our parents chose to live in. It’s a unique context that we’re lucky to share, and I’m proud of myself for connecting with it unabashedly and on my own terms. I’d much rather spell out “P-R-E-E-T” every time I meet someone than be confined to an unfinished story or my good name.

And allow me to finish that story. If you’ve read this far, you might be wondering why my parents gave me the nickname “Justin” in the first place. It actually wasn’t an anticipatory whitewashing, as many have assumed or believed over the years. Upon a visit back to India a few years ago, my dad’s best friend told me the tale — while my dad and his friends awaited my birth at the hospital area, the receptionist’s voice called out “the baby is just in.” My dad and uncles, who had been pregaming my birth, excitedly repeated the phrase “JUST IN! JUST IN! JUST IN!”

And the rest was history.

Love it, Jaspreet!! Keep sharing your perspective and stories. I can see one day you publishing a NY times bestseller!!!